GROUP-ing my thoughts on GROUP theory

table of contents

introduction

As 2025 begins (after what I perceive to be a not-so-good finals week) and people are out and about living it up outside (or inside, if that’s what you prefer), I decided it would be an optimal use of my time to understand the premise of Group Theory. More explicitly, I am just here to answer the question “what is Group Theory and why is it so useful?”, since, even after completing Maths 320, I still struggle to explain real-world applications of this topic and its importance in Mathematics.

This is a big, big problem as I am the (self-imposed) “#1” group-theory “fan” and to be able to retain such a title, I must at least have some fundamental understanding of what group-theory is before coming up with some legible argument as to why group-theory is the greatest of all time.

so what is group theory?

A quick browse of any basic definition of ‘group theory’ will most likely net you two possible explanations:

wait, what are groups?

Now, the definition of a group is a:

Group:

A non-empty set of elements, , with an operation, , that takes two elements of and combines them to produce another element of .

The set of elements has to satisfy the axioms (established properties) below:

- associativity - for any in , we have

- identity - there exists an identity element, , such that

- inverse - for any element in the set, , there will always exist an inverse element, commonly denoted , such that

At first glance, this definition does not provide much intuition for what its use cases are, nor does anything mention anything about symmetries in particular.

hmm, what about symmetries then?

In fact, the symmetry we talk about is slightly different from the geometrical definition that most people have been exposed to, as it is generally defined as:

Symmetry:

a collection of all the operations that preserves an object’s underlying structure (basically, leaving the object unchanged).

Using geometrical symmetry as an example, rotations and reflections are symmetry operations as a , , or degree rotation or a reflection across either of the diagonals of a square will leave it looking the same as before.

huh, what is the relationship between groups and symmetry then?

To put it simply, Groups are just an abstraction of symmetry.

and, what does that mean exactly?

The definition of “abstraction” that Wikipedia supplies is that:

Abstraction:

process of extracting the underlying structures, patterns or properties of a mathematical concept, removing any dependence on real world objects with which it might originally have been connected, and generalizing it so that it has wider applications

Whilst you could read this definition and make the argument that mathematics itself is an abstraction, an example of an abstraction that we use on a daily basis would just be numbers.

Take the number 4 for example; when we have 4 apples, 4 houses or 4 successful mathematicians, we see that the number itself is not attached to any physical object in particular,

but is just there to represent the quantity of objects present.

In essence, numbers abstract away from the specific nature of each objects involved and provide us with a universal framework to manipulate quantities.

In fact, if you take a step back and revisit the definition of a group, you can view it as a way of formalizing the essential rules of symmetry:

Group:

A non-empty set of elements, , with an operation, , that takes two elements of and combines them to produce another element of .

- a symmetry of an object combined with another symmetry will always result in another symmetry

The set of elements has to satisfy the axioms (established properties) below:

- associativity - for any in , we have

- symmetries are associative as it does not matter how we group them; as long as the order of the operations are preserved, the end result will remain identical

- identity - there exists an identity element, , such that

- the identity element (keeping the object fixed) is always a symmetry

- inverse - for any element in the set, , there will always exist an inverse element, commonly denoted , such that

- any symmetry should be reversable by just “undoing” the symmetry

In other words, since groups aim to abstract away from the particularities of all the objects involved, you can view the definition of a group as an attempt to formalize the essential rules of symmetry:

wait, why do we want to abstract symmetry in the first place?

The occurence of symmetry is suprisingly common, from the shape of snowflakes, to its presence in architectural design and even bell ringing.1 The beauty of abstraction is that once you generate an abstract definition for a concept, any time these properties are satisfied, you can apply the same reasoning, tools, and theorems across a wide variety of situations.

could I get examples of appearances of symmetry?

Important disclaimer:

Even though this was the perfect segway for me to start rattling through a lot of Group Theory’s significant use-cases in science, after trying to disect and summarise Galois Theory in a digestable manner for non-mathematicians, I realised that I would not be doing any of these topic’s justice if I were to try and summarise whole undergraduate courses in singular paragraphs.

From Galois Theory in Algebra to the Lorentz group in Physics, all of these topics definitely each deserve at least their own blog post (or multiple) which is half the reason why I decided to leave out some more monumental discoveries that were made using group theory, and decided to explore some niche applications of group theory.2

take the rubik’s cube as an example

When you shuffle the cube from it’s “solved” position, the result is one of the many shuffled positions of the cube that it could take. To reach such a position, there will always exist a set of moves of the cube that you can take to reach it. In order to solve the cube, you can simply reverse the set of moves you took to shuffle it in the first place (proving the existence of an inverse). Clearly, the identity element is just its solved state (proving identity), concatenating any position (or move sequence) together with another just results in another valid position (proving closure) and as long as the order of the move sequence remains constant, the ending position will remain the same as well (proving associativity).

As a result, there exists a Rubik’s Cube Group where each element of the Group is a unique position of the cube.

Understanding the Rubik’s Cube Group proved highly valuable, particularly in determining God’s Number. Morwen Thistlethwaite is recognized for his mathematical approach, which used group theory to develop a method capable of solving any 3x3 cube in at most 52 moves.

In 1981, this was quite an important theoretical break-through as it intends on slowly reducing the cube to subgroups (subsets of the original groups, that satisfies all the conditions of a group) of the original Rubik’s Cube group that only contains positions which can be solved without, for example, using quarter turns of the upper and bottom face. With the further optimisation of the Thistlewaite Algorithm, and improvement to computing technology, several researchers were able to eventually deduce that God’s Number is 20.

or the fifteen puzzle

A much simpler example to consider would be the fifteen puzzle.

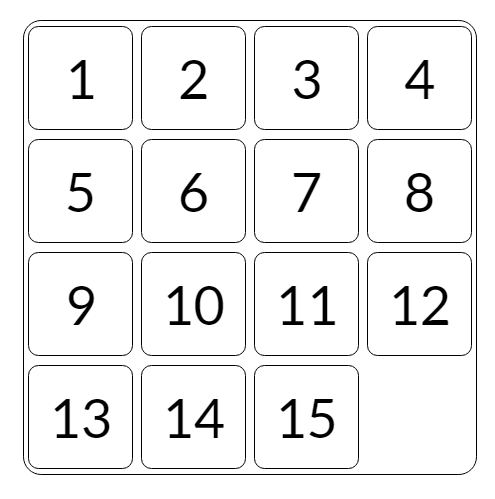

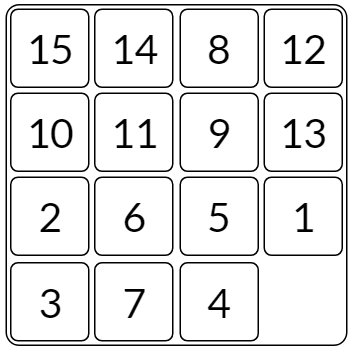

For those unaware, the fifteen puzzle is a 4x4 sliding puzzle containing tiles ordered from 1 to 15, where the goal is to order the tiles into numberical order. Whilst it is definitely possible to trivialise the puzzle by splitting the puzzle into sub-problems, how would you determine if any provided configuration of the fifteen puzzle is solvable or not? We will start by attempting a simpler problem from Sam Loyd, where he posed a wager for $1000 to anyone that could provide a solution to the fifteen puzzle with the position of 14 and 15 interchanged.

Similar to the Rubik’s Cube, we can follow similar steps to show that all possible configurations of the fifteen puzzle can be arranged into a group (identity, inverse, associtivity, closure).

However, the one caveat to this approach is that not all movesets can be composed one after each other; if you want to compose move B after move A, that is only possible if move A leaves the puzzle where the empty slot is in a legal position for move B to be applied (forming a Groupoid, instead of a Group).

Hence, if we restrict all possible movesets to always leave the empty slot in the bottom right corner, we will find that each position follows the ruleset of a group structure. In fact, by using properties derived from a well-studied group, we can show that, with the position of 14 and 15 interchanged, the fifteen puzzle is unsolveable.

We will start off by defining a permutation of a set, , as a one-to-one mapping from the set to itself. Using the position below as an example, we can describe the permutation using the function such that:

In fact, we can define each permutation using a “two-line notation” with the top line defining the original “slot” and the second line to define the tile that is currently occupying the slot. Using the above example, we get:

However, every permutation can also be represented in cycle form.

Seeing that slot 1 has tile 15, slot 15 has tile 4, slot 4 has tile 12, and so on, we can more compactly represent the permutation in terms of disjoint cycles.

Note, that any cycle containing a point that is mapped to itself can just be omitted (e.g. is the same as ).

The intuition for reading permutations in cyclic form is that you read from right to left. For example, if we were to take the number 15, you check each cycle from right to left until you reach one with inside of it; once you do reach one, , then the cycle sends to . You now repeat these steps for the remaining cycles with the number until you reach the end. Thus, giving us the result that the permutation sends to (you can check this with every number from to and will see that it matches every value in the “two-line” notation).

These cycles can then be further reduced to transpositions (or cycles of length 2). For example,

Using a similar method to before, you can prove for equality by seeing if the permutation sends each number in the same way: e.g. for , the cycle sends to , then the cycle sends to before reaching the end, meaning the RHS permutation sends to .

Therefore, by reducing the original cycle notation, we can rewrite it in terms of 13 transpositions:

Similar to the fact that integers have parity (odd/even), permutations also have parity:

Note that like how an integer can not be simultaneously even and odd, permutations can also not be simultaneously even and odd (meaning if you can write a permutation in terms of a product of an odd number of transpositions, you can only write it as a product of an odd number of transpositions).

Then, since the permutation is clearly odd, if we can prove that all possible permutations of the fifteen puzzle are even, we can prove that it is impossible to win $1000 from Sam Loyd.

This turns out to be quite intuitive if you just pay attention to how the empty slot moves when you shuffle the puzzle. Since the empty slot will always have to return back to the bottom right position, you realise that for any up movement, there will be a corresponding down movement, and for any left movement, there will be a corresponding right movement. Since every move is paired and we can represent each move by a transposition (since each move we make swaps the tiles on 2 adjacent slots), it means that no matter what permutation the puzzle ends up in, we know that it must be able to be written in terms of an even number of transpositions.

Thus, this informally proves that the permutation is impossible to achieve.

Why do we need to know all this? One of the most fundamental groups, the finite symmetric group, , is used to represent all the possible permutations possibly performed on elements. Intuitively, that implies all the possible permutations of the fifteen puzzle is a subgroup of the finite symmetric group.

In fact, it has been proven that each permutation correlates to a well-known group, (or the alternating group of degree 15), which is a finite set that consists of all the even permutations in the corresponding finite symmetric group. You can read more about the fifteen puzzle and its relation to the alternating group of degree 15 here.